Nabokov on translation

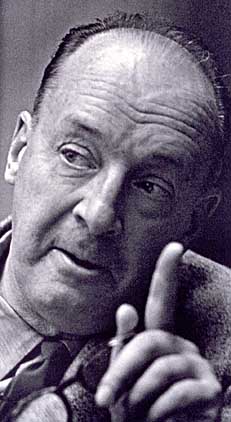

Vladimir Nabokov is fond of literal translations—and he is certainly someone we should pay attention to.

Vladimir Nabokov is fond of literal translations—and he is certainly someone we should pay attention to.

The Nov. 7, 2005 issue of the New Yorker, in a great article by editor David Remnich entitled “The Translation Wars”, from which much of the content of this post is lifted, talks about Nabokov’s ideas on translating, from Russian to English in particular.

Personally, I concur wholeheartedly with Cervantes, who is quoted in the article:

Reading a translation is like looking at the Flanders tapestries from behind; you can see the basic shapes but they are so filled with threads that you canot fathom their original lustre.

I myself have viewed many such tapestries from the rear.

Now on to Nabokov. He says of all the sins of a translator

The third, and worst, degree of turpitude is reached when a masterpiece is planished and patted into such a shape, vilely beautified in such a fashion as to conform to the notions and prejudices of a given public. Ths is a crime, to be punished by the stocks as palgiarists were in the show-buckle days.

He goes on to say that when translating his intent is to provide the reader with a literal-minded “crib, a pony. And to the fidelity of transposal I have sacrificed everyhting: elegance, euphony, clarity, good taste, and even grammar.”

So he’s “transposing” now, instead of “translating”? He captured his philosophy of translation in a pithy poem, also published in the New Yorker, way back in 1955:

What is translation? On a platter / A poet’s pale and glaring head, / A parrot’s speech, a monkey’s chatter, / And profanation of the dead. / The parasites you were so hard on / Are pardoned if I have your pardon, / O Pushkin, for my strategem. / I travelled down your secret stem, / And reached the root, and fed upon it; / Then, in a language newly learned, / I grew another stalk and turned / Your stanza, patterned on a sonnet, / Into my honest roadside prose—/ All thorn, but cousin to your rose.

The noted critic Edmund Wilson (Wikipedia), Nabokov’s erstwhile friend, begged to differ. Reviewing Nabokov’s translation of Pushkin’s Onegin (Wikipedia ), he accused him of “bald and awkward language”, a desire to “torture both the reader and himself”, “sado-masochism”, “actual errors in English”, an “unnecessarily clumsy style”, “vulgar” phrases, inaccurate transliteration, a “lack of common sense”, and “serious failures of interpretation”. Hmmm. Sounds like some Dogen translations I know. (Later Wilson admitted that these criticisms were “more damaging” than he had intended.)

This tension between literal and interpretive translations pervades the entire translation world as it applies not just to novels but even computer manuals. (I don’t think I’d like my Japanese digital camera to come with a manual translated by the Nobel laureate author of “Lolita”.) But one can’t help feeling that the people having this war of words are missing the point—or at least failing to clearly state, or more likely understand, the groundrules: the nature and intent of translation itself.

I’m deeply interested in this discussion because I’ve translated, and am still translating, the 13th-century Japanese Zen master Dogen. The more I work on Dogen, the more I move toward the interpretive side. In the next post, I will go through a specific passage from Dogen as a means to shed light on the true nature of the interpretive decisions the translator must make, across the entire lexical/syntactic/semantic spectrum, and how they relate to the purpose and meaning of the translation.