Neurotheologians as sports commentators

Are you studying to be a neurotheologian, but worried about your future career prospects? Now you may be able to find high-paid work as a commentator on sports figures’ religious experiences!

Are you studying to be a neurotheologian, but worried about your future career prospects? Now you may be able to find high-paid work as a commentator on sports figures’ religious experiences!

Baseball fans will not soon forget the miraculous come-from-behind victory by the Boston Red Sox in the 2004 World Series. It was the first world championship for the Sox in 86 years.

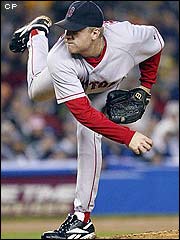

In Game 6, Curt Schilling took the mound for the Sox, defying predictions that the torn tendon sheath in his ankle would prevent him from pitching. Instead, the doctors basically stapled his tendon down so it wouldn’t flap around and Schilling went out to pitch, bleeding visibly around the ankle. His famous “bloody sock” was later donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Before the game, we are told, Schilling, devastated by his loss in Game 2, “surrendered to the Lord”, although he is not normally a very religious person. Then, in the fifth inning, a runner on second, Schilling had a major religious epiphany. “Something” (“somebody”?) “told” him not to make the pick-off throw he had been planning and instead pitch to the batter, who promptly lined into a double play, ending the Yankees’ threat.

“I just laughed,” Schilling says. “I couldn’t deny Him now.” After the game, he told the other players, “It wasn’t me. It was all God.”

To explain what was going here, the editors of Best Life, a men’s magazine, turned in their June, 2005 issue to Andrew Newberg . How did they find him? Well, successful neurotheologians all have agents these days.

Newberg started them off with a sort of Neurotheology for Dummies-level overview:

The images [of people meditating] revealed distinct changes in the temporal lobes, suggesting a neurological basis for these types of occurrences. But that doesn’t mean people’s interpretations are wrong. “We can see what the brain was doing.” Newbert says, “but we can’t see if God was there.”

I see. Newberg proceeds to explain his basic theory of religious experience:

When these spiritual events occur, the frontal lobes block incoming sensory information from reaching the parietal lobes, where the information would be processed. The results is a loss of the sense of self and a feeling of deep connectedness to nature or to God, explains Newberg.

Fine, but how is this related to Schilling?

This kind of episode can occur spontaneously in a stressful situation like Curt Schilling’s, when the autonomic nervous system is kicked into high gear. The heightened arousal (caused by stress), combined with a lack of sensory information to the parietal lobes, leads to a sense of peacefulness, of connectedness to something greater than the self—exactly what Schilling describes.

An often-overlooked benefit of being stressed out all the time: all those bonus spiritual experiences.

“Schilling’s not a Buddhist or Hindu, so he’s not going to have a Buddhist interpretation of that experience,” says Newberg. “He’s Christian, so his interpretation is that God was with him.”

But there was a key element missing from Newberg’s explanations. Seeing God out there on the ballfield is well and good, but how did those deprived parietal lobes contribute to Curt being able to make the right pitch to get the guy out? Come on, Andy, give us a little more body/mind here.

Another great career opportunity for neurotheologians, especially here in Hollywood, is as consultant to the entertainment industry. When neurotheology enters the mainstream in a big way, we’ll find neurotheological elements all over the movies and TV. Then there’s also this neurotheology Nintendo game I have designed, where you try to keep all your brain chemicals in balance for that really big religious explosion…gonna be a big hit.