Religion in the minimally conscious

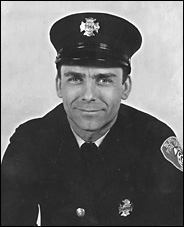

May 4th, 2005 Donald Herbert, a fireman, suffered brain damage during a fire, was in a coma for 2½ months, then emerged into a period of “faint” or “minimal” consciousness, where he stayed for more than nine years until “waking up” and reconnecting to his family and friends on May 2, 2005.

Donald Herbert, a fireman, suffered brain damage during a fire, was in a coma for 2½ months, then emerged into a period of “faint” or “minimal” consciousness, where he stayed for more than nine years until “waking up” and reconnecting to his family and friends on May 2, 2005.

“Minimal consciousness” is defined as being aware, but unable to communicate.

See MSNBC report.

Damaged brains like Herbert’s have provided us with many clues about neural functioning (perhaps to the extent that we are overly dependent on that type of analysis). Neurologists will be certainly studying him in an attempt to understand what mechanism could account for his recovery. (Three months earlier, he had been started on a cocktail of three medicines usually used to treat Parkinson’s, ADHD and depression, intended to stimulate neurotransmitters.)

Our interest, though, is neurotheological. How did Herbert’s brain damage, his period of minimal consciousness, and his recovery affect his religiosity, if at all?

We know that loss of consciousness occurs in epileptic seizures, which in turn have been tied to religious or pseudo-religious experience.

In Herbert’s case, as the neurons in the higher levels of his brain were regenerating and weaving themselves together for nearly a decade, while he lay in bed mutely watching TV, finally reaching the critical mass necessary for the restoration of consciousness, did they also recreate the cortical pathways necessary for religious belief and experience? Is Herbert more or less religious now than he was before his accident?

I enter the church and take my seat among the faithful. The priest flips a switch, and the chapel is bathed in a sea of multicolored lasers, sending the worshippers into a deep, healing, unified, spiritual state.

I enter the church and take my seat among the faithful. The priest flips a switch, and the chapel is bathed in a sea of multicolored lasers, sending the worshippers into a deep, healing, unified, spiritual state. “From Joseph’s descriptions of his experiences, he does not fit the pattern neurotheologians believe they have found for ‘religious experiences.’”

“From Joseph’s descriptions of his experiences, he does not fit the pattern neurotheologians believe they have found for ‘religious experiences.’” In

In

I ran across the work of

I ran across the work of  After grabbing a deputy’s gun and shooting her and a judge in a courthouse, a bad guy in Atlanta took Ashley Smith hostage in her apartment. The plucky girl, unfazed, whipped out her copy of

After grabbing a deputy’s gun and shooting her and a judge in a courthouse, a bad guy in Atlanta took Ashley Smith hostage in her apartment. The plucky girl, unfazed, whipped out her copy of