Landmark Forum: a religiobiological perspective (II)

Monday, January 24th, 2005This post continues our project, which started with this post, of adopting the religiobiological stance in looking at the Landmark Forum.

Therapy. Especially in the earlier periods, the Forum focuses on your human relationships, notably broken ones. It urges you to patch things up now with that estranged father or sister, to the point of calling them on your cell phone during the next break. Participants then volunteer to stand in front of the group and talk about these personal problems, resulting in some riveting Dr. Phil moments, in no small part thanks to the savvy, unyielding, quick-on-the-feet, penetrating probing of the facilitator.

Examples:

- the boy who finally forgave his mother and father for trying to raise him white, even though he was obviously mixed, the product of his mother’s amorous dalliance with a black lover

- the distraught wife who forgave herself for exposing her two small children to the horribly traumatic experience of 30 FBI agents bursting into their house at 6am to arrest her drug-dealing husband, whom she had believed when he said he was going straight

- slightly less tragically, the girl who wondered why her boyfriend wouldn’t commit when all she had done was left him at the altar two years earlier

- finally, the boy whose Hispanic father abandoned him, completely alone, to wander the streets, at the age of 9

These stories are moving to the point of tears.

It is this aspect of Landmark that has led some to categorize it as a form of large-group awareness training. Being in front of a large audience, and getting their feedback, unquestionably raises the efficacy of this therapeutic process. And I personally have no doubt that many of these people underwent genuine transformations, although as with most transformations there is the danger of backsliding and need for consolidation that one hopes some kind of follow-up would address.

From a religiobiological standpoint, to my knowledge no has elucidated the neurological mechanism underlying emotional fixations or constantly revisited past traumas—this was the project, after all, that Sigmund Freud gave up on. At the risk of circularity, it would seem undeniable that there is some such schematic substrate which is altered by emotional catharsis. There is little doubt that such catharsis, and thus such neurological changes, are experienced by some Landmark attendees, although probably just those who take advantage of the opportunity to “share” in front of the group and have the benefit of direct interaction with the leader. (The conclusion for would-be Landmark attendees would to be sure to “share”.)

However, there is more to the process of personal growth than merely breaking through emotional pathologies. The breaking through is better seen as a kind of necessary first step, like removing a tree that’s blocking the road. As I interpret the structure of the three-day Landmark experience, and in light of the fact that the emotional components come earlier in the training, that’s also how Landmark itself positions it. So while we can note the apparent success of these dramatic five-minute metamorphoses for those who participate in them, and hypothesize that they are having some kind of neurobiological effect, this alone is not sufficient to conclude that Landmark’s overall effectieness is religiobiologically plausible.

We will continue our examination of Landmark in one final post. But before we leave the topic, what about the issue mentioned by one reader, that a huge majority of attendees surveyed said that the Forum changed their lives for the better?

These survey results deserve close scrutiny. There is no baseline to compare against, the results are completely self-reported, and there is a built-in bias on the part of the participants towards justifying their own expenditure of time and money. At a minimum, they would need to normalized against results from participants in other programs or religions. For instance, how many Baptists feel that their religion improves their lives?

The study in question was apparently carried out by IMC, Inc., but who paid for it? Like any survey, the results can be spun in a number of ways. For instance, the Yankelovich survey reported that “more than 30% of participants thought the Forum did poorly or only fairly in improving their overall effectiveness” (my wording).

The numbers are also biased to the extent the participants are self-selected. For what it’s worth, the largest percentages are 25-34, some college. Another study revealed that prospective participants were significantly more distressed than than their peers and had a higher level of impact of recent negative life events. I am merely saying that the results should be interpreted in this context.

Finally, a note on the positioning of this entire endeavor. I am not trying to criticize Landmark or praise it or say it is good or bad. The point is simply to examine it to see if there are any obvious aspects which could tie in with a neurologically-based theory of religion or personal development. As a reader rightly pointed out, if we find no such aspects, and we haven’t yet, that could just as easily be interpreted as casting doubt on the religiobiology project as a whole or as indicating that there may be types of religious/developmental phenomenon that do not have neural correlates, as that Landmark is unlikely to actually be as effective as claimed.

Does Landmark Forum seem likely to affect your brain? If so, how? This question is an example of the

Does Landmark Forum seem likely to affect your brain? If so, how? This question is an example of the  Is God an accident? That’s the title of an article by

Is God an accident? That’s the title of an article by  Bill O’Reilly (picture;

Bill O’Reilly (picture;  The religiobiological stance is a framework for peering into phenomena that lie at the boundary of religion and biology, or are suspected to. This stance is at the heart of Numenware. The religiobiological stance is an approach which starts with the assumption that there are biological underpinnings to religious experience, and analyzes issues based on that assumption.

The religiobiological stance is a framework for peering into phenomena that lie at the boundary of religion and biology, or are suspected to. This stance is at the heart of Numenware. The religiobiological stance is an approach which starts with the assumption that there are biological underpinnings to religious experience, and analyzes issues based on that assumption. Does your brain have a neuron for recognizing Halle Berry’s face? Or Bill Clinton’s? My brain seems to have one for Reese Witherspoon, but that’s another post.

Does your brain have a neuron for recognizing Halle Berry’s face? Or Bill Clinton’s? My brain seems to have one for Reese Witherspoon, but that’s another post. Are high altitudes conducive to revelations and other spiritual experiences, and if so, why? That’s the topic of a recent

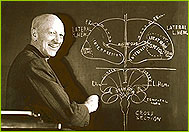

Are high altitudes conducive to revelations and other spiritual experiences, and if so, why? That’s the topic of a recent  Every neuroscience undergraduate learns about the Penfield map, a correspondence between locations on the stripe across the middle of the top of the brain (

Every neuroscience undergraduate learns about the Penfield map, a correspondence between locations on the stripe across the middle of the top of the brain ( A new course at the University of Florida,

A new course at the University of Florida,