Another reference to "go" in Dogen?

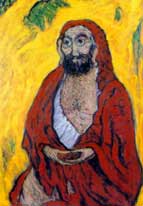

January 23rd, 2005 In the “Twining Vines” (Katto) fascicle of his Shobo Genzo, Dogen retells the story of how Bodhidharma (image), on his deathbed, queried his four disciples as to their understanding. The first three gave verbal answers, to which Bodhidharma replied that they had attained his skin, flesh, and bones, respectively. Eka (Huike), in contrast, simply prostrated himself three times (awkwardly, one imagines, since he was missing an arm) and returned to his place. Commenting “You have got my marrow”, Bodhidharma then annointed him his successor.

In the “Twining Vines” (Katto) fascicle of his Shobo Genzo, Dogen retells the story of how Bodhidharma (image), on his deathbed, queried his four disciples as to their understanding. The first three gave verbal answers, to which Bodhidharma replied that they had attained his skin, flesh, and bones, respectively. Eka (Huike), in contrast, simply prostrated himself three times (awkwardly, one imagines, since he was missing an arm) and returned to his place. Commenting “You have got my marrow”, Bodhidharma then annointed him his successor.

Dogen’s point here is that Eka was not being “rewarded” for giving the “right” or “best” answer.

According to the Nishijima/Cross translation, where the name of the chapter is infelicitously rendered as “The Complicated”:

Now, learn in practice, the First Patriarch’s words “You have got my skin, flesh, bones and marrow” are the Patriarch’s words. The four disciples each possess what they have got and what they have heard. Both what they have heard and what they have got are skin, flesh, bones, and marrow which spring out of body and mind, and skin, flesh, bones, and marrow which drop away body and mind. We cannot see and hear the ancestral Master only by means of knowledge and understanding, which are but one move in a go game—not one-hundred-percent realization of subject-and-object, that-and-this.

Leaving aside the stiltedness of the translation, was Dogen really referring to the game of go here? (See another post regarding Dogen and go.) It seems unlikely. The Japanese in question is itchaku-shi (一著å?). According to John Fairbairn, an expert in archaic Chinese and Japanese, it could “mean one piece, one seed, one son, etc.—or just a pawn = something nugatory”. In other words, a single element, or perhaps “scrap”, which is what I will use below.

The go image is admittedly attractive—comparing our cerebral understanding to one move out of the hundreds that constitute a go game, presumably representing the vast range of types of perception and realization. Unfortunately, it seems that Nishijima/Cross simply invented this.

I would translate this section as follows:

Make no mistake, Bodhidharma meant just what he said: “You have attained my skin/flesh/bones/marrow”. Indeed, everything the four disciples queried by Bodhidharma had either experienced or learned was precisely the skin, flesh, bones and marrow from which body and mind spring forth and drop away. They could not have entered the presence of the venerable master with mere scraps of opinions and logic, for then the question of doing vs. being could not have been adequately illuminated.

Continuing (my translation):

Some may think that some of the four disciples were closer to the truth in their understandings and that Bodhidharma, implying there were degrees of profundity in skin/flesh/bones/marrow or that skin and flesh is more distant from the truth than bones and marrow, recognized Eka’s attainment of the marrow because his understanding was superior. Sadly, however, such people, having yet to learn the ancestors’ way of study, miss Bodhidharma’s true message.

Is God an accident? That’s the title of an article by

Is God an accident? That’s the title of an article by  What can hypnosis teach us about how people’s pre-formed views influence their interpretation of the world?

What can hypnosis teach us about how people’s pre-formed views influence their interpretation of the world? If neurotheology’s basic premise holds water, then a healthy brain is essential to a healthy spirit. And what better food to feed the brain than sushi, that quintessential Japanese classic, marrying the fruits of the sea and the rice paddy? Besides, it tastes good.

If neurotheology’s basic premise holds water, then a healthy brain is essential to a healthy spirit. And what better food to feed the brain than sushi, that quintessential Japanese classic, marrying the fruits of the sea and the rice paddy? Besides, it tastes good. I am pleased to announce the first annual neurotheology market size survey.

I am pleased to announce the first annual neurotheology market size survey. Bill O’Reilly (picture;

Bill O’Reilly (picture;  Terry Schiavo is the brain-dead woman whose husband is trying to take her off life support, while her parents try to keep her alive.

Terry Schiavo is the brain-dead woman whose husband is trying to take her off life support, while her parents try to keep her alive.