Tom Coburn (R-OK) on life and death

January 16th, 2005 Unique insights on life and death from one of the Senate’s leading lights.

Unique insights on life and death from one of the Senate’s leading lights.

Tom Coburn (picture; official website) is the Republican Senator from Oklahama whose website says his priorities include “representing Oklahoma values.” Apparently Oklahama values include homophobia: during the 2004 campaign, he alerted Oklahomans to “rampant lesbian debauchery” in the state and warned that “[the gay] agenda is the greatest threat to our freedom that we face today.” And eugenics: Coburn sterilized under-age girls (he’s an MD) without their consent; in one case he says he got “oral consent” but “the nurse forgot” to get it written down.

During the Senate hearings on the confirmation of John G. Roberts Jr. as the 17th Chief Justice of the United States. Coburn took a break from the crossword puzzles he was caught doing during the opening statements to actually “question” the nominee:

Would you agree that the opposite of being dead is being alive?

My my, do we have a philosopher for a Senator here? The unnerving thing is that Roberts actually paused before answering, “Yes,” belatedly adding “I don’t mean to be overly cautious in answering it.”

But Coburn was not actually trying to philosophize about life and death, of course; he was just laying the groundwork for some simplistic posturing and blustering on the abortion issue:

You know I’m going somewhere. One of the problems I have is coming up with just the common sense and logic that if brain wave and heartbeat signifies life, the absence of them signifies death, then the presence of them certainly signifies life.

Hmmm. This is not only overly black and white, but also incoherent. He’s given two criteria, but what about the case where only one is present, such as Terri Schiavo (Wikipedia)? By this logic, does he think she was neither alive nor dead? And where do being pre-alive or pre-dead or in between dead and alive or dead but about to come back to life fit into this picture?

Undeterred, Coburn continues his muddled train of thought:

But for the listeners of this hearing, if, in fact, life is the presence of a heartbeat and brain wave, it’s important for everybody in the country to know that at 16 days post-conception, a heartbeat is present; and that at 41 days, right now, we can assure ourselves that brain activity and brain waves are present.

But if the heart doesn’t start beating until 16 days after conception, why is he against the morning-after pill? By his logic, isn’t the fetus “dead” at that point? (Too bad there’s not a morning-after pill for Senate elections.)

And as the technology improves, we’re going to see that come earlier and earlier.

Huh? Technology is going to make babies in the womb start having a heartbeat earlier?

I make that point because so many of the decisions of the Supreme Court have been made in a vacuum of the scientific knowledge of what life is, when personhood is, when it begins, when it doesn’t, when it exists, when it doesn’t.

So “scientific knowledge” is going to tell us “what life is” or “when personhood is” or “when it begins” or “when it doesn’t”? I’ll have to alert the scientists so they can get cracking on this. And by the way, what does “when personhood doesn’t begin” mean anyway?

And so that was for your information and my ability to put forth a philosophy that I believe would solve a lot of the controversy in this country.

In other words, thanks for listening to my confused monologue and the controversy would be solved if everyone agreed with my jumbled thinking.

I would certainly hope that our electoral system is still functional enough to wash away detritus like this. Then again, America gets the public servants it wants and deserves.

Senator, let me help with that six-letter word starting with A for 8-down: it’s ADDLED.

My

My

Today is the 60th anniversary of the

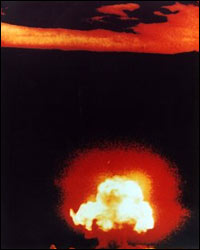

Today is the 60th anniversary of the  The cans taken to Portland and from there by train to Los Angeles on February 2, 1945, contained the first few grams of Hanford plutonium, laboriously extracted from the uranium isotopes produced in the reactors. In California, the cans were turned over to a junior army officer from Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the actual bomb was to be constructed. By May 1945, a system was in place where regular shipments of Hanford plutonium were being made to Los Alamos, using one-kilogram jugs that looked like big thermos bottles, in convoys protected by submachine guns. The scientists at Los Alamos labored mightily and finally produced a test bomb containing Hanford plutonium at its core, which they named “Gadget.” It was detonated at the Trinity Test Site near Alamagordo, New Mexico at 5:29:45 a.m. on July 16. Seeing the detonation,

The cans taken to Portland and from there by train to Los Angeles on February 2, 1945, contained the first few grams of Hanford plutonium, laboriously extracted from the uranium isotopes produced in the reactors. In California, the cans were turned over to a junior army officer from Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the actual bomb was to be constructed. By May 1945, a system was in place where regular shipments of Hanford plutonium were being made to Los Alamos, using one-kilogram jugs that looked like big thermos bottles, in convoys protected by submachine guns. The scientists at Los Alamos labored mightily and finally produced a test bomb containing Hanford plutonium at its core, which they named “Gadget.” It was detonated at the Trinity Test Site near Alamagordo, New Mexico at 5:29:45 a.m. on July 16. Seeing the detonation,  Gambari is one of those uniquely Japanese-flavored words you’ll never be able to translate into English for the simple reason that the concept—an effort which is sustained, slightly stubborn, and perhaps just marginally excessive—doesn’t really exist in our culture. Gambari evokes images of a race—not a dash, but a marathon. Gambari assumes that the probability of winning is somewhat low—an underdog flavor—but that there is realistic hope of doing so if all goes well, although that is not the overriding goal, gambari being its own reward. Gambari has a payoff which is often far down the road, a road on which lurk any number of obstacles, large and small.

Gambari is one of those uniquely Japanese-flavored words you’ll never be able to translate into English for the simple reason that the concept—an effort which is sustained, slightly stubborn, and perhaps just marginally excessive—doesn’t really exist in our culture. Gambari evokes images of a race—not a dash, but a marathon. Gambari assumes that the probability of winning is somewhat low—an underdog flavor—but that there is realistic hope of doing so if all goes well, although that is not the overriding goal, gambari being its own reward. Gambari has a payoff which is often far down the road, a road on which lurk any number of obstacles, large and small. Gabyo is one of my favorite Dogen essays. Literally, it means “painted ricecake”, but I would update that and call it “drawing donuts”. In this chapter of Shobo Genzo, Dogen ponders the meaning of the ancient Chinese saying that a painted ricecake cannot satisfy your hunger—or, as I would say, a drawing of a donut can’t fill you up.

Gabyo is one of my favorite Dogen essays. Literally, it means “painted ricecake”, but I would update that and call it “drawing donuts”. In this chapter of Shobo Genzo, Dogen ponders the meaning of the ancient Chinese saying that a painted ricecake cannot satisfy your hunger—or, as I would say, a drawing of a donut can’t fill you up.

Think of meditation in the same way you think of flossing.

Think of meditation in the same way you think of flossing.

And there’s definitely a woman’s hand visible in the visionary new plan that Sanyo announced. There were the obvious things, such as cutting debt, selling stuff, shuttering factories, firing people, cutting costs. What’s more interesting is the new Sanyo vision: Think

And there’s definitely a woman’s hand visible in the visionary new plan that Sanyo announced. There were the obvious things, such as cutting debt, selling stuff, shuttering factories, firing people, cutting costs. What’s more interesting is the new Sanyo vision: Think