Zen-Brain Reflections is James Austin’s follow-up to “Zen and the Brain.”

Zen-Brain Reflections is James Austin’s follow-up to “Zen and the Brain.”

Austin’s work and study has led him to a deep understanding of what it means to translate ancient philosophical texts. Below I quote at length from his discussion of translating the Sandokai by Sekito (Shih T’ou) (p. 330; my emphasis, slightly edited for clarity):

Can any translation today have the same meaning as did the original, a work composed of only 220 Chinese characters? Suppose you were to insist on having only a direct, literal translation of each original Sino-Japanese ideogram. It would be a crude version in broken pidgin English. Professional translators can only be humbled by all the major compromises they have had to make. Beyond the basic problem, the casual Western reader may not suspect how many other major semantic compromises can enter in.

Begin with the title itself. One soon discovers that this same Sino-Japanese title has been translated into English in diffferent ways. Some options from our own era are

- coincidence of difference and sameness

- merging of difference and unity [Loori]

- inquiry into matching halves

- realizing unity [Cleary]

- the coincidence of opposites

- the harmony of difference and equality [Shunryu Suzuki]

- the identity of relative and absolute [Glassman]

and so on.

The above examples suggest that different translators…might have chosen to insert aspects of either their own private experience, or earlier personal opinions, or even some doctrinal belief system into a given phrase. Moreover, each translator can have several other subjective needs…

Let us be more specific, citing only a few potential conflicts that a contemporary translator might need to resolve. Must I adhere rigidly to literal interpretations, to traditional doctrinal formulas (and often multiple footnotes) to remain within acceptable scholarly traditions? Or can I remain true to what experience tells me is the direct, immediate flash of Zen insight itself? Because surely this deepest experiential truth entails letting go of my own tendencies…to attach arcane, dated references that overburden a line and blur the central message.

Nor do the translator’s conflicts and compromises end there. Can I still be true to those few old original ideograms, yet express their flowing spirit and intent in a readable contemporary literary style? Furthermore, must I conspire with the original author in old mystifications , thereby perpetuating the notion that everything about Zen is forever mysterious, if not unknowable?

Austin then proceeds to give his own translation of the Sandokai, which, although I know little Chinese and have never studied this poem in detail, appears to be a major improvement over existing translations in terms of both fidelity and readability

Here is an aspect of translation that often goes unnoticed, whether the document in question is a philosophical tract or a computer manual: the fluent translation is often actually more accurate. In other words, sloppiness on the part of the translator in understanding the original text tends to be correlated with sloppiness in rendering that understanding into the target language.

I’ll have more on Austin’s new book in the coming weeks.

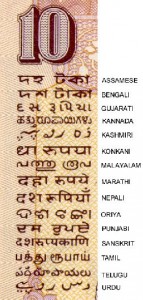

I’m extremely pleased to announce the on-line availability of my important proposal for a major reform of Japanese orthography:

I’m extremely pleased to announce the on-line availability of my important proposal for a major reform of Japanese orthography:  I’ve often thought over the years of coming up with a new ideographic written language. Now I find a man named Charles K. Bliss has already done this, creating something called Blissymbols (or “Semantography”).

I’ve often thought over the years of coming up with a new ideographic written language. Now I find a man named Charles K. Bliss has already done this, creating something called Blissymbols (or “Semantography”).