Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion (Amazon) is a snappy, readable book about, basically, how God doesn’t exist (or exists only with vanishingly low probability). Greater minds than my own have already reviewed the book (NYT ) and pronounced it brilliant or stupid or flawed or whatever. Here I’ll confine myself to neurotheological and Buddhist aspects.

Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion (Amazon) is a snappy, readable book about, basically, how God doesn’t exist (or exists only with vanishingly low probability). Greater minds than my own have already reviewed the book (NYT ) and pronounced it brilliant or stupid or flawed or whatever. Here I’ll confine myself to neurotheological and Buddhist aspects.

The most basic problem with this book is that it completely fails to take into account the connection between religion and any process of personal development and/or the biological “correlates” of that process. To the extent religion is to some extent a highly corrupted version of meaningful, biologically-based insights about how to be happier, many of Dawkins’ points would need to be modified or recast.

On p. 37 Dawkins claims he will not be “concerned at all with other religions such as Buddhism or Confucianism. Indeed, there is something to be said for treating these not as religions at all but as ethical systems of philosophies of life.” That’s a great distinction to be made, but at the same time Buddhism and Western monotheism are similar in that they are both socially dominant systems of belief and thought, and rather than arbitrarily excluding one, why doesn’t Dawkins incorporate Buddhism into his thinking as a way to better define the topological contours of religion and religious behavior ?

Surprisingly for a biologist, Dawkins mentions “neurotheology” only once, in a dismissive tone. On pp. 168-169, he says:

The proximate cause of religion might be hyperactivity in a particular node of the brain. I shall not pursue the neurological idea os a ‘god centre’ int he brain because I am not concerned here with proximate questions…If neuroscientists find a ‘god centre’ in the brain, Darwinian scientists like me will still want to understand the natural selection pressure that favoured it.

This seems like a particular devious way to dodge neurotheological questions. Perhaps the existence of a ‘god centre’ (more accurately, religiously-connected neural circuitry or structures) can be considered a “proximate” issue, but attempting to understanding it, rather than simply ignoring it, could help in grasping the “ultimate” cause, which for Dawkins is the Darwinian one. Would Dawkins focus on the evolutionary reason for the existence of the visual faculty without bothering to learn about the structure of the eye?

The cutest idea in this book, new at least to me, is that religion survives due an evolutionary tendency for children to believe what their parents say. This provides a scenario for a gradual decline over decades and centuries of Bible-thumping religions, as in each generation some percentage of believers, however, small, discard the religion of their parents and produce non-religious kids, as I did—to the extent that one day my oldest son came home from elementary school and asked me, “Daddy, who is this guy they were talking about in class today called ‘Cheeses’?”. Compare this to Dennett in Breaking the Spell, who provides no roadmap other than that people will or should stop believing just because he thinks religion is so stupid.

Note: to counter comment spam, hyperlinks in comments have now been disabled. To include a link in comments, please simply specify the URL, and the reader will have to cut and paste.

LSD and other pyschotropic drugs (including DMT; previous post) are likely to play a key role in any neurotheology research program. They evoke behaviors and experiences which clearly have much in common with the religious and are experimental design-friendly.

LSD and other pyschotropic drugs (including DMT; previous post) are likely to play a key role in any neurotheology research program. They evoke behaviors and experiences which clearly have much in common with the religious and are experimental design-friendly.

The magazine Utne has a series of articles in its June 2006 issue relating to topics such as neuroethics and neural implants. The one of interest to us,

The magazine Utne has a series of articles in its June 2006 issue relating to topics such as neuroethics and neural implants. The one of interest to us,  Giuseppe Pagnoni of Emory University (pictured) is doing fMRI studies of zazen (

Giuseppe Pagnoni of Emory University (pictured) is doing fMRI studies of zazen ( Richard Davidson, the Dalai Lama collaborator who scanned Tibetan monks’ brains, was named to the

Richard Davidson, the Dalai Lama collaborator who scanned Tibetan monks’ brains, was named to the  Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion (

Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion ( Mario Beauregard has fMRI’d nuns having semi-mystical states and found that a whole range of brain regions (including the right medial orbitofrontal cortex, right middle temporal cortex, right inferior and superior parietal lobules, right caudate, left medial prefrontal cortex, left anterior cingulate cortex, left inferior parietal lobule, left insula, left caudate, left brainstem, and extra-striate visual cortex), demonstrating that mystical experience (or at least the memories of mystical experience these Christian nuns called forth) were involved, thus supposedly disprovnig the “God spot” theory.

Mario Beauregard has fMRI’d nuns having semi-mystical states and found that a whole range of brain regions (including the right medial orbitofrontal cortex, right middle temporal cortex, right inferior and superior parietal lobules, right caudate, left medial prefrontal cortex, left anterior cingulate cortex, left inferior parietal lobule, left insula, left caudate, left brainstem, and extra-striate visual cortex), demonstrating that mystical experience (or at least the memories of mystical experience these Christian nuns called forth) were involved, thus supposedly disprovnig the “God spot” theory.

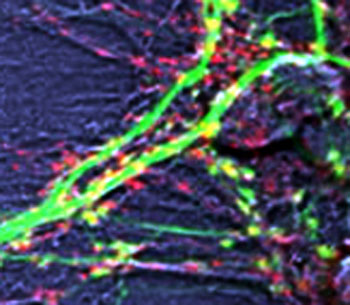

Neuroplasticity is a plausible—some might say obvious—hypothesis for the mechanism by which humans develop spiritually. For instance, the relatively slow speed of neurogenesis would account for the time required under development protocols such as meditation.

Neuroplasticity is a plausible—some might say obvious—hypothesis for the mechanism by which humans develop spiritually. For instance, the relatively slow speed of neurogenesis would account for the time required under development protocols such as meditation.