Neurotheology and gender

Tuesday, May 10th, 2005 A few years ago I attended a talk given by two Zen masters, one male, one female. The man, going first, retold and analyzed some ancient Chinese koan in very Zen master-like fashion. The woman, when her turn to talk came, just sat there silently for a while, then burst into tears. Regaining her composure a bit, she sobbed, “I’m just so happy that I can be here with you all. It brings my practice to life.” She went on to share with us her personal relationship with that zen community, and the frustration she felt at having only blunt, dualistic, verbal tools at her disposal to communicate her insights with us, then cried some more. Finally she flopped over and leaned into the male master sitting at her side, throwing her arms around him.

A few years ago I attended a talk given by two Zen masters, one male, one female. The man, going first, retold and analyzed some ancient Chinese koan in very Zen master-like fashion. The woman, when her turn to talk came, just sat there silently for a while, then burst into tears. Regaining her composure a bit, she sobbed, “I’m just so happy that I can be here with you all. It brings my practice to life.” She went on to share with us her personal relationship with that zen community, and the frustration she felt at having only blunt, dualistic, verbal tools at her disposal to communicate her insights with us, then cried some more. Finally she flopped over and leaned into the male master sitting at her side, throwing her arms around him.

We all have similar experiences in our own religious traditions of the difference between what men and women take from the religion, what they emphasize.

We know almost as little about the neuroscience of gender as we do about the neuroscience of religion. But perhaps we can overlay our sparse knowledge of the two fields to generate some new insights.

For instance, what are the neurotheological implications of the well-known research concerning the relative size of the third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH-3), showing that it’s more than twice as large in men as in women (and homosexual men)? Could this be related to the hypothalamus’ role in the fear response, and thus connected to the informal observation that men’s relation to religion is more often one of “fear and awe” than women’s “love and compassion”?

To build robust neurotheological models, we need every clue we can get. Hopefully our expanding understanding of the neurological differences between the sexes can be one fruitful source of such clues.

One high-level hypothesis that should be part of a neurotheology research plan is this: religious practices such as meditation give rise to persistent neurological changes. Although most studies to date have focused on neurological changes during meditation, research such as

One high-level hypothesis that should be part of a neurotheology research plan is this: religious practices such as meditation give rise to persistent neurological changes. Although most studies to date have focused on neurological changes during meditation, research such as  In

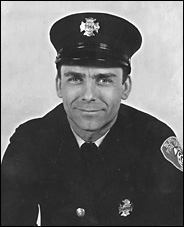

In  Donald Herbert, a fireman, suffered brain damage during a fire, was in a coma for 2½ months, then emerged into a period of “faint” or “minimal” consciousness, where he stayed for more than nine years until “waking up” and reconnecting to his family and friends on May 2, 2005.

Donald Herbert, a fireman, suffered brain damage during a fire, was in a coma for 2½ months, then emerged into a period of “faint” or “minimal” consciousness, where he stayed for more than nine years until “waking up” and reconnecting to his family and friends on May 2, 2005. I enter the church and take my seat among the faithful. The priest flips a switch, and the chapel is bathed in a sea of multicolored lasers, sending the worshippers into a deep, healing, unified, spiritual state.

I enter the church and take my seat among the faithful. The priest flips a switch, and the chapel is bathed in a sea of multicolored lasers, sending the worshippers into a deep, healing, unified, spiritual state. “From Joseph’s descriptions of his experiences, he does not fit the pattern neurotheologians believe they have found for ‘religious experiences.’”

“From Joseph’s descriptions of his experiences, he does not fit the pattern neurotheologians believe they have found for ‘religious experiences.’” In

In

I ran across the work of

I ran across the work of  After grabbing a deputy’s gun and shooting her and a judge in a courthouse, a bad guy in Atlanta took Ashley Smith hostage in her apartment. The plucky girl, unfazed, whipped out her copy of

After grabbing a deputy’s gun and shooting her and a judge in a courthouse, a bad guy in Atlanta took Ashley Smith hostage in her apartment. The plucky girl, unfazed, whipped out her copy of